The Batak script is a writing system used to write the Austronesian Batak languages spoken by several million people on the Indonesian island of Sumatra. The script may be derived from the Kawi and Pallava script, ultimately derived from the Brahmi script of India, or from the hypothetical Proto-Sumatran script influenced by Pallava.

Medan is the capital and largest city of the Indonesian province of North Sumatra. The nearby Strait of Malacca, Port of Belawan, and Kualanamu International Airport make Medan a regional hub and multicultural metropolis, acting as a financial centre for Sumatra and a gateway to the western part of Indonesia. About 60% of the economy in North Sumatra is backed by trading, agriculture, and processing industries, including exports from its 4 million acres of palm oil plantations. The National Development Planning Agency listed Medan as one of the four main central cities in Indonesia, alongside Jakarta, Surabaya, and Makassar. In terms of population, it is the most populous city in Indonesia outside of the island of Java. Its population as of 2023 is approximately equal to the country of Moldova.

Minangkabau is an Austronesian language spoken by the Minangkabau of West Sumatra, the western part of Riau, South Aceh Regency, the northern part of Bengkulu and Jambi, also in several cities throughout Indonesia by migrated Minangkabau. The language is also a lingua franca along the western coastal region of the province of North Sumatra, and is even used in parts of Aceh, where the language is called Aneuk Jamee.

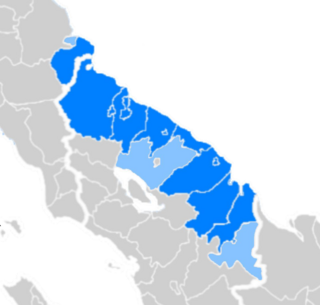

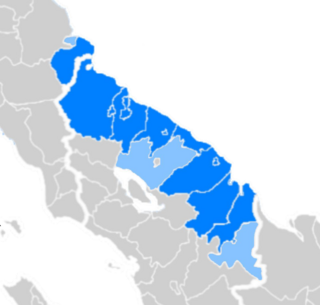

North Sumatra, also called North Sumatra Province, is a province of Indonesia located in the northern part of the island of Sumatra, just south of Aceh. Its capital and largest city is Medan on the east coast of the island. It is bordered by Aceh on the northwest and Riau and West Sumatra on the southeast, by coastlines located on the Indian Ocean to the west, and by the Strait of Malacca to the east.

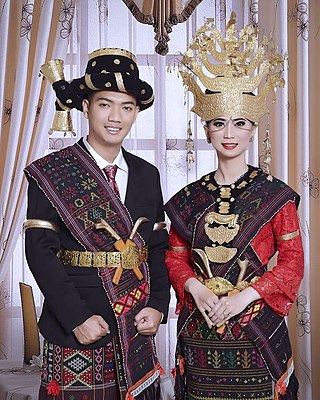

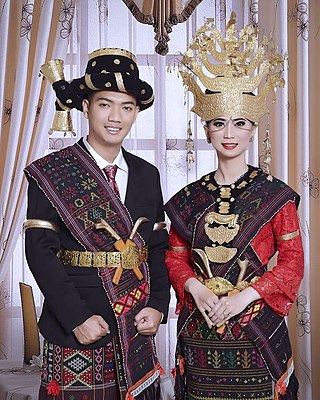

Batak is a collective term used to identify a number of closely related Austronesian ethnic groups predominantly found in North Sumatra, Indonesia, who speak Batak languages. The term is used to include the Karo, Pakpak, Simalungun, Toba, Angkola, and Mandailing, related ethnic groups with distinct languages and traditional customs (adat).

Pematangsiantar, and also known as the City of Pematangsiantar, is an independent city in North Sumatra Province of Indonesia, surrounded by, but not part of, the Simalungun Regency, making Pematangsiantar an enclave within Simalungun Regency. Pematangsiantar formerly had the status of a second-level district and was the administrative centre of the surrounding Regency, but in 1986 it was elevated to Kota (City) and separated from the Regency.

Padangsidimpuan is a city in North Sumatra, Indonesia, and the former capital of South Tapanuli Regency, which surrounds the city. It has an area of 159.28 km2 and a population of 178,818 people at the 2000 census, which rose to 191,554 in the 2010 census and 225,105 at the 2020 Census; the official estimate as at mid 2023 was 236,217 - comprising 119,228 males and 116,989 females.

The Batak languages are a subgroup of the Austronesian languages spoken by the Batak people in the Indonesian province of North Sumatra and surrounding areas.

The Mandailing are an ethnic group in Sumatra, Indonesia that is commonly associated with the Batak people. They are found mainly in the northern section of the island of Sumatra in Indonesia. They came under the influence of the Kaum Padri who ruled the Minangkabau of Tanah Datar. As a result, the Mandailing were influenced by Muslim culture and converted to Islam. There are also a group of Mandailing in Malaysia, especially in the states of Selangor and Perak. They are closely related to the Angkola and Toba.

Toba Batak is an Austronesian language spoken in North Sumatra province in Indonesia. It is part of a group of languages called Batak. There are approximately 1,610,000 Toba Batak speakers, living to the east, west and south of Lake Toba. Historically it was written using the Batak script, but the Latin script is now used for most writing.

North Padang Lawas is a landlocked regency in the North Sumatra province of Indonesia. It has an area of 3,918.05 km2, and had a population of 223,049 at the 2010 census and 260,720 at the 2020 census; the official estimate as of mid-2023 was 275,448. North Padang Lawas Regency was created on 17 July 2007 from the eastern parts of the South Tapanuli Regency. Its administrative seat is the town of Gunung Tua.

South Tapanuli is a regency in North Sumatra, Indonesia. Its seat is the town of Sipirok. This regency was originally very large and contained thousands of towns and villages, including the city of Padang Sidempuan. The areas that have separated from South Tapanuli Regency are the new regencies of Mandailing Natal, Padang Lawas Utara, and Padang Lawas, all lying to the south-east of the residual South Tapanuli Regency, plus the city (kota) of Padang Sidempuan. After the division, the regency seat moved from Padang Sidempuan to Sipirok.

Toba Batak people are the largest ethnic group of the Batak peoples of North Sumatra, Indonesia. The common phrase of ‘Batak’ usually refers to the Batak Toba people. This mistake is caused by the Toba people being the largest sub-group of the Batak ethnic and their differing social habit has been to self-identify as merely Batak instead of ‘Toba’ or ‘Batak Toba’, contrary to the habit of the Karo, Mandailing, Simalungun, Pakpak communities who commonly self-identify with their respective sub-groups.

Simalungun, or Batak Simalungun, is an Austronesian language of Sumatra. It is spoken mainly in Simalungun Regency and Pematang Siantar, North Sumatra, Indonesia.

Angkola people are part of the Batak ethnic group from North Sumatra who live in the South Tapanuli regency. The Angkola language is similar to Mandailing language also with Toba language, but it is sociolinguistically distinct.

Willem Iskander (1840–1876) was an Indonesian writer, nationalist, teacher and educator. He advocated for native Indonesian education in Dutch colonial times from North Sumatra. He founded Teacher Education School in 1862 in Tano Bato, Mandailing Natal Regency.

Kualuh Malay, also known as North Labuhanbatu Malay, is a variety of Malay used in the southeast right on the east coast of North Sumatra, used as a mother tongue by the Malay community there. It has a clear affinity with Panai Malay to the south and may still interact to a high degree with other east coast Malay varieties. It is mainly used in North Labuhanbatu Regency, the former territory of the historical Malay Sultanate of Kualuh which lasted until 1946, after its destruction due to the East Sumatra revolution. The area of use covers the lower to upper areas of the Kualuh River, where in the Na IX-X district, this language is very influenced by the Batak languages, with its accent being very visible.